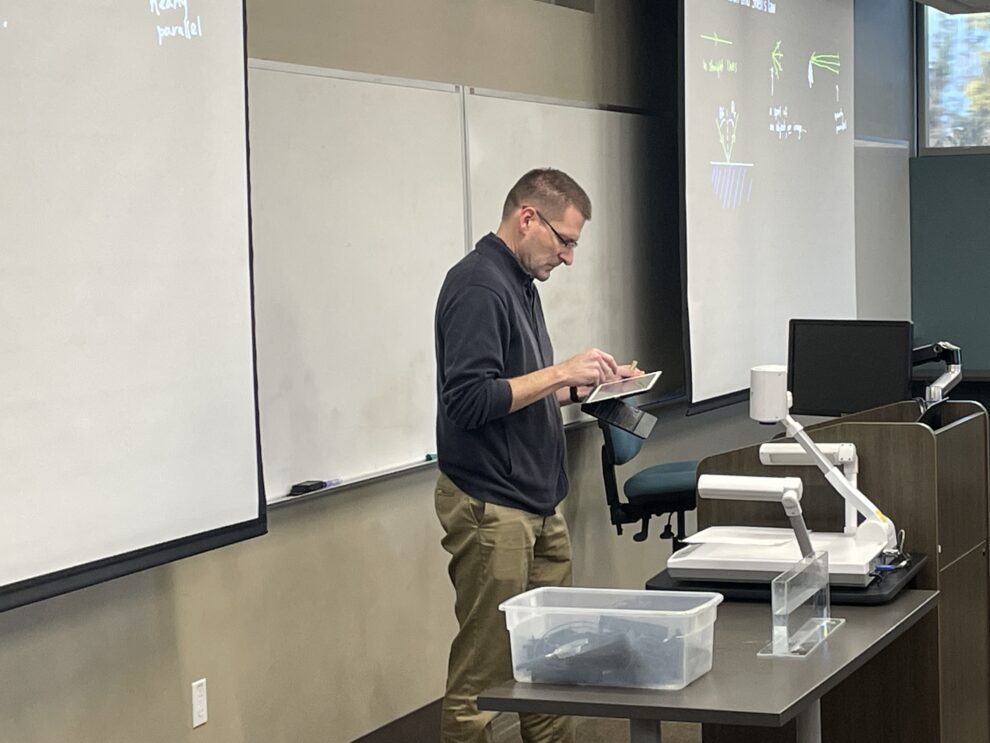

Paul Schmelzenbach is a professor of physics at Point Loma Nazarene University who teaches Foundation Exploration courses in addition to specialized classes for physics and engineering majors. According to third-year biology major Ella Carlos, Schmelzenbach has a reputation for making physics courses accessible for any type of student, which is why the Point sat down with him to talk about his approach to teaching and physics.

The Point: You teach a few G.E. courses, like The Cosmos and General Physics. How do you approach those classes where students might not be interested in physics?

Schmelzenbach: Well, I think it helps that I love physics. I’ve found, even with topics I don’t find interesting at first, if somebody else finds it interesting it’s a lot more interesting to me. Why is it interesting to that person? Even if I walk away later not loving a particular subject, I think I gain some insight by sharing the enthusiasm. So, I try to make that come across and that’s easy enough because I love it, so it’s not like I have to fake it. I think that’s the number one key to teaching classes or parts of those classes that I find most interesting. I think that probably comes across to students. I know for me, [when I’m] learning, it does.

TP: You also teach Physics of Sound and Music and you play the trumpet, is the science of music one of those areas that becomes easy to teach because you’re interested in it?

PS: I would say the motivation for the class, and Cosmos also, is that it’s easier to learn about a subject like science or physics if you have a starting point of something that’s interesting to you. With [the Cosmos Class], almost everybody’s a little interested in space. I could be wrong, but at some point in everybody’s life they think: “Oh, that’s kind of cool.” I think music is one of those things also; everybody likes music somehow. Now, they might not like the same kind of music I do, or they might not play an instrument, or they might not have a musical skill, but it seems like nearly everyone listens to music. That’s a really neat entry into thinking of physics: to look at something that’s interesting and see what more we can learn about it.

TP: How do you approach students who aren’t used to the subject or who might be intimidated by math?

PS: I try to think of what it is I’m trying to convey. So, the math itself could be working with numbers– dividing, multiplying and square rooting– but often [math] is more like representing something. So there’s a lot of good pictures that you can understand without even understanding the math, but you come away with a deeper understanding and that’s a good connection point. If you can make a different representation, even if you don’t understand the math, you come away with something deeper.

I think it’s a good reminder for me that we all have things we’re not good at. I’ve practiced a lot with math, so it comes easily, but I’ve struggled with learning another language. A few years ago I tried to learn Korean, and I still don’t know much Korean, but I felt like I learned a lot and it was good to remind myself that things can be hard when you first try it and there are some things that I’ll just never quite have a knack for, but I can gain some appreciation for it. So I try to keep things in my life that are hard for me to do.

I think truly listening [is important to teaching physics] too, because sometimes I get so excited talking about something, but I try to really see what a student is understanding and then come alongside them. That’s actually pretty cool because I’ll find new ways I see something because a student just comes from a different, fresh point of view. If someone doesn’t understand something, I think: “How can I explain it another way?” Or sometimes a student just has a misconception, but oftentimes they bring in a different perspective.

The physics of music class is a good example. There are many musicians who know a lot more about the theory of it, or they have a knack for it, so it’s neat to interact with them and they’ll see connections, or we’ll make connections together. They’ll teach me a little bit about something and hopefully they can learn something from the class too. Everybody comes in from different perspectives; they’ve been in the world a long time and know a lot of things. Sometimes it doesn’t match with what the tests end up on, so that’s frustrating in college, but you can learn something from anybody.

TP: Why do you think students can get intimidated by physics classes?

PS: I think there’s a question of: “What is physics?” If you haven’t had physics before it might seem hard or like there’s a lot of math, or maybe you had some background and it was hard, so we purposefully have some different levels of physics you can engage in. There are some that assume you have a mathematical background because you can learn a lot of cool things that way, but then we purposefully have some classes that allow you to see through the lens of physics, and I know I’m highly biased but it’s so cool! How could you not love this?

Some students might be surprised by how much they enjoy aspects of physics. It’s one of my favorite things when students will say: “I was afraid of taking this class but after the first few days it was actually kind of fun.” I’ll have students come back years later and say: “Dr. S, as I was driving I thought of this physics concept” and it’s interesting when you start thinking about a [new] way of looking at the universe. That becomes part of your daily life in some ways. When you look at the sunset you enjoy the beauty of the sunset and that’s amazing in itself, but then there’s sometimes a part of my mind that flips over into asking why it’s like that. Knowing how much more amazing it is, the particulates and different scattering that’s happening, that additional way of thinking about the universe provides a little extra bit of coolness.

Written By: Lily Damron