Part I: Before There Was a Blunt… There Was A Point

The college was on unstable ground. A once-stout Nazarene college that sat northeast of Los Angeles in Pasadena decided to move to San Diego in 1973, drawing more than just Nazarenes. Their new campus sat on Sunset Cliffs, a dreamy oceanfront property that brought surfers and Nazarenes alike to the newly named Point Loma College (PLC): An Institution of the Church of The Nazarene.

The move couldn’t have come at a more socially intense period. Fresh out of the 1960s cultural revolution, the 1970s were just the next step in a radical socio-political attitude. An attitude especially poignant among the youth.

PLC didn’t lack its fair share of radicals; one being Michael Christensen, third-year english-literature major and editor-in-chief of The Point. In the spring of 1976, Christensen and The Point began to challenge the severe administration at the time and the inequities taking place on campus, specifically surrounding dorm policies.

“Men had no restrictions, they could go to Tijuana, they could get drunk. Women had to have dorm hours, so they had to be in at a certain time.” Christensen said.

The Point also challenged the university on issues such as dress code, dancing and drug use. The college had very little tolerance for the questioning and bending of these rules. If there was a violation, it usually resulted in expulsion from the college.

“You could be in the religion department and teach that God was a fraud before you could go dancing,” said Steve Thames, then feature editor of The Point.

Christensen also published a weekly column titled “As I See It” — in it he would tackle an issue on campus and share his opinion about it. The Point published several satirical pieces as well, which featured characters such as “Nancy Nazarene” and “Melvin Manuel III.” Neal Putnam, an investigative reporter for The Point, wrote “The Hot Seat” — a column that asked questions to an administrator or faculty member every week.

Christensen did not lead up. His satirical piece, “The Art of Seduction,” got The Point shut down by the college administration early in the spring semester of 1976. To top it off, Christensen was dismissed as the editor-in-chief for disciplinary reasons after a student accused him of drinking an alcoholic beverage off campus over winter break.

“The Dean of Students [Jim Jackson] was careful to say ‘it’s unrelated to your editorial policy.’ Which I didn’t think it was and no one believed that,” Christensen said.

Naturally, this irked a number of students, especially those on The Point staff. Much of the staff was cordial outside of the newsroom, leading to friendships and long nights of ranting about their distaste for the authoritative Nazarene staff that ruled over them and shut down their newspaper.

Among them was Steve Thames, who suggested one day in his quad at Young Residence Hall that they should start publishing an underground newspaper. Friends of Christensen and Thames, Susan Agee Borland and Lionel Yetter suggested the name “The Blunt” — the opposite of a point.

Part II: The Blunt

The idea was ambitious. For starters, the small group of students had little funding to start this underground newspaper. The students could also have faced severe punishment mostly at the hands of Dean of Students James Jackson.

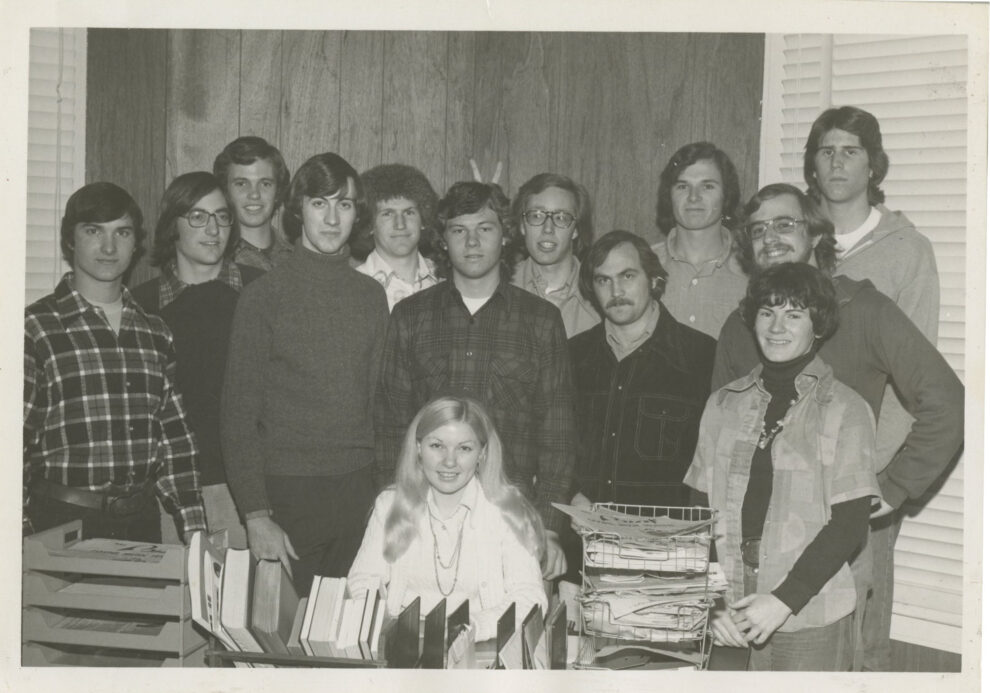

Regardless, the radicals on campus started to form a staff for their underground newspaper with Steve Thames and Calvin Slater at the helm as co-editors. The rest of the staff consisted of other former Point staff members and students interested in the free-thinking mindset of their constituents.

“There ought to be a place for dissenters and radicals in a Christian college. This underground newspaper gave us a vehicle to continue writing,” Christensen said.

The financing wasn’t as tricky as they thought it would be. Student Michael McCafferty paid for virtually everything.

“His family, at the time, had some disposable income,” Thames said.

A few other students sold ads for The Blunt to cover costs. Primarily Neal Putnam and Lionel Yetter. Putnam had experience with selling ads for The Point and found that many of the advertisers for The Point wanted to take part in advertising for The Blunt.

“I happened to be a volunteer with the Gerald Ford election campaign and I knew some of the people running the local campaign, so I got a paid political ad to run in The Blunt. I was actually very proud to get it in The Blunt, and I was told by the local campaign that they sent a copy of The Blunt to The White House at the time as well as the national campaign headquarters.” Putnam said.

After covering the cost, the dissenters took to writing. Some of the writers included Barbi Roth, who was dubbed the “raving reporter” for The Blunt. Sylvia Mokhtarian-Parsons was passionate about free speech and independent journalism. Students, Susan Agee Borland, Carol Foster-Breeze and Allan Woods were all instrumental in the publication of The Blunt and battling for free press on the Point Loma College campus.

All the while, the Bluntees, as they call themselves, kept the publication of The Blunt quiet. However, they needed people around campus whom they could trust. They decided to select people at every dorm that would be able to distribute the paper under students’ doors.

After the first edition was complete, McCafferty, alongside his disposable income, rented a limousine and the Blunt staff loaded up around 1200 copies of The Blunt in the back of the limo. Early in the morning, around 2 a.m., the Blunt staff distributed the papers to the dorms and slipped a copy of The Blunt under each student’s door. A student with the group had keys to the admin building and put copies in each faculty inbox.

When the PLC student body woke up they were greeted by a satirical, almost insulting newspaper put together by a ragtag group of their peers. The Blunt featured satirical pieces like Thames’ “Why I’m Not a Nazarene” written by “JC,” columns, news briefs and cartoons poking fun at the administration.

“When we went to class and went to chapel, the place was buzzing,” Thames said.

Among the upset were James Jackson and College President Shelburne Brown. According to Thames, the Bluntees invited President Brown to lunch to discuss The Blunt. The talk went well but Brown walked away from that conversation thinking the students wouldn’t publish again.

But the students continued to defy. They published again in May, shortly before the end of the semester.

“We were pretty rude about some things,” Thames said.

The administration had little tolerance for the second issue and sent out letters to all of the writers featured in The Blunt’s byline, essentially dealing them expulsion and inviting them to reapply in the fall.

McCafferty hired an attorney and brought him into a meeting with Dean Jackson and President Brown. Brown didn’t show up but Jackson stayed and cited that he was personally attacked by students writing in unsigned articles. He claimed that this was unethical and McCafferty’s attorney agreed and left the meeting as well.

Both Calvin Slater and Steve Thames transferred and chose not to reapply, while the rest of The Bluntees reapplied for the fall semester.

The Point was resurrected in the fall but not under the jurisdiction of Christensen or any other Bluntee. The Bluntees all graduated and went their separate ways, some staying in journalism, others having long, successful careers in law or becoming professors, occasionally meeting together when they could.

The Blunt was laid to rest. That was until 30 years later.

Part III: The Blunt Stays Sharp

At a Blunt reunion in 2004, Carol Foster-Breeze proposed the Blunt scholarship. The scholarship was dedicated to students who have the same spirit as the Bluntees who proposed an underground newspaper at Young Hall in the spring of 1976.

The scholarship was fully funded in 2012 and continues to award students who live and write radically. Nearly 50 years later the Bluntees continue to meet when they can and still have a fondness for the work they did together at PLNU.

The 2024 Blunt Scholarship is now open until April 1.

According to the Blunt Scholarship Agreement 4.b,“The purpose of the Blunt Scholarship is to support witty, gifted, and idealistic students with a radical edge who write and publish their work. The ideal candidate will be someone with intellectual curiosity, who is well read, socially conscious, and who has formed opinions and beliefs that challenge the status quo. Candidates should feel a sense of responsibility to the larger community and have thought about their relationship to it.”