Editor’s Note: This article contains spoilers.

“Sunrise on the Reaping,” Suzanne Collins’ latest release in the “Hunger Games” series, which was published on March 18, takes a probing look at the power of propaganda by showcasing its effect on different groups of people.

As Collins is commonly known for writing in response to current events, this intentional focus for the second installment of her recent return to the series should not be treated as the flippant theme of an inconsequential teen novel.

While the original “Hunger Games” trilogy focused on the brutality of the system and the cruelty of the games, “Sunrise” dug into the disparity between the events of the games, the parade, the reaping and the version of events that was broadcast to the nation.

District 12 and the Capitol are wallpapered in propaganda posters that declare, “NO PEACE, NO PROSPERITY! NO HUNGER GAMES, NO PEACE!”

No one in the districts believes this. The message is meant for any well-cushioned Capitol citizen harboring moral qualms with the games. But it doesn’t matter that the poor, hungry and disenfranchised don’t buy into the propaganda because they don’t have the power to do anything about it.

Before the games begin, the tributes in costumes are paraded through the Capitol in chariots, during which an audience member hurls a firework at District 12’s chariot. Their poorly trained horses go into hysterics, hurtle past drunken spectators down the parade route and throw the tributes to the ground, killing one of them.

Despite an abundant amount of witnesses, the version of the parade broadcast to the nation is a lie in which all goes smoothly. The dead tribute is not acknowledged and is replaced by a body double, who looks the same as her predecessor but has a limited vocabulary and a listening device in her ear.

It is obvious to everyone who knew her that she had been replaced, but the lie works because everyone who knew her is powerless. Likewise, the parade attendees who know the broadcast is a farce either don’t care, don’t have the power to do anything or both.

In their respective games, the series’ main characters, Katniss Everdeen and Haymitch Abernathy, commit acts of treason in rebellion against the cruelty of the games. Haymitch calls these “posters,” as they are intended to counteract the propaganda posters about the Hunger Games ensuring peace. But where Katniss times her acts of kindness and rebellion so they have to be on camera, Haymitch’s flashier moments get edited from Panem’s screens, and his family is silently and brutally punished for them.

“Sunrise on the Reaping” displays a spectrum of responses to the lies and propaganda, ranging from people in the districts who roll their eyes or live in fear to Capitol citizens who embrace the messaging and enjoy the spectacle of the games.

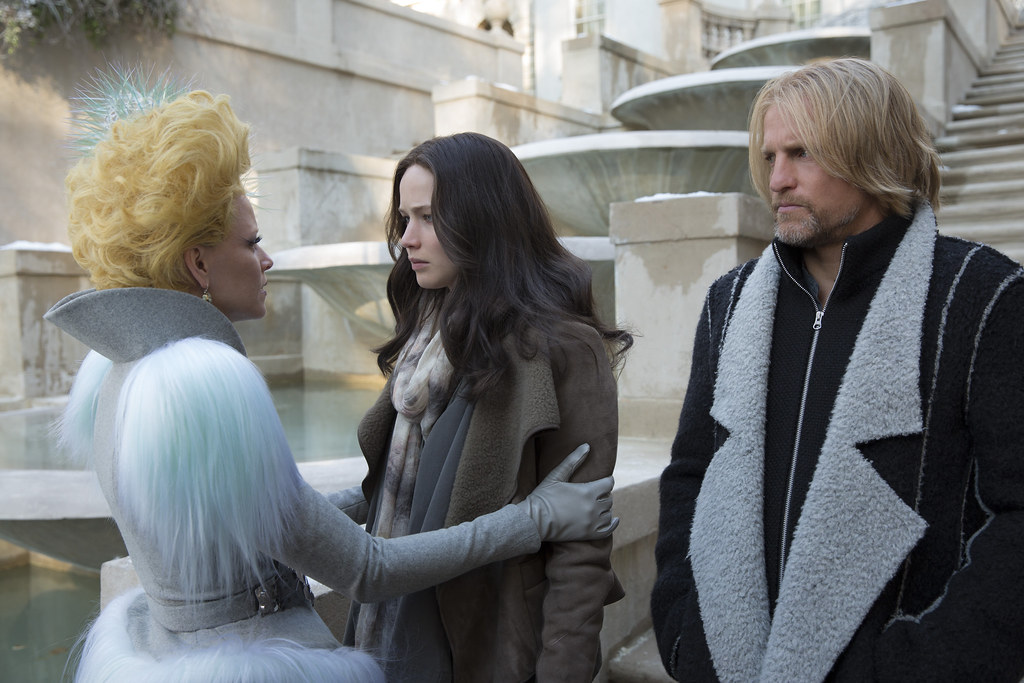

The take I found the most chilling was that of character Effie Trinket, from the original trilogy, who makes a reappearance. She has more compassion than most for the District 12 tributes, who she can see have been treated especially poorly due to their district’s reputation as the poorest and least likely to produce a victor.

She dresses them in her relative’s clothes when their stylist is nowhere to be seen, and she even defies peacekeepers’ orders so she can stay with Haymitch before his final interview. However, right after she tells him, “I know your position could not have been easy,” she says, “But, [the Hunger Games] really are for a greater good,” showing that despite her benevolence, the Capitol has made her into a tool for their cruel spectacle, nullifying what good she could have done in a different world.

This is exactly Collins’ point; there will always be excuses to do nothing. In any world, there will be lies grappling for the attention of people with vaguely good intentions, especially those who are powerless when alone but could move mountains together.