The quarantined student was interviewed by The Point upon her release by the Wellness Center after testing negative for COVID-19.

While COVID-19 may make it hard to breathe, so does anxiety. How do students coping with mental illness handle the psychological toll of quarantine?

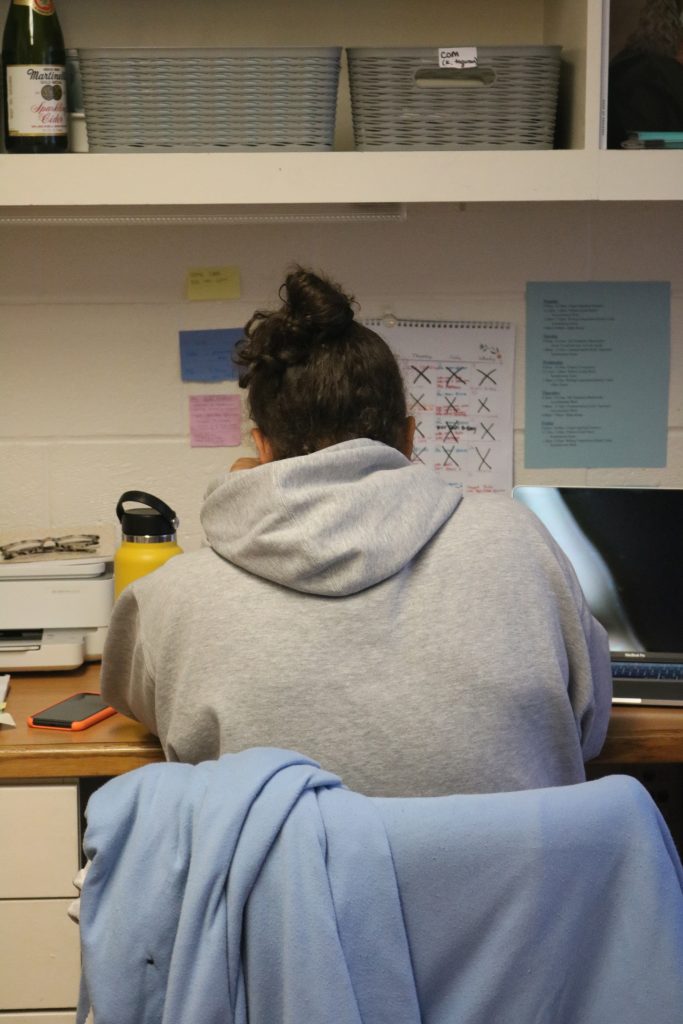

Point Loma Nazarene University freshman Dezi Wells was placed into quarantine when another student, who tested positive for COVID-19, listed her as someone they had been in recent contact with.

Wells said, “The nurses were saying that I had spent more than 15 minutes and was less than six feet way from someone who tested positive who was not wearing a mask.”

This high level of exposure warranted Wells’ quarantine, but she said, “I was not either of those things. I wasn’t that close; we were both wearing masks; we were outside; it was nowhere near six feet.”

With two conflicting stories, nurses sided with the student who tested positive for COVID-19, so Wells was placed in quarantine.

“I was super angry. I felt betrayed and that no one was listening to me,” Wells said. “My mental health was already a struggle because of my anxiety and depression, so quarantine was harder for me to accept.”

Since Wells tested negative for COVID-19, she was placed in quarantine but not in isolation. Isolation at PLNU means students are housed in isolated rooms with access to a bathroom, shower and kitchenette. Wells was allowed to leave her room to do laundry, go to the bathroom, get water, use the kitchen and take out her garbage.

Wells said, “When I would take my garbage out I would walk on the cliffs. I very, very, very slowly walked back inside from taking out my trash.”

Over the course of her isolation experience, she tested negative for COVID-19 three times. Each day was different, but she described her average daily experience in quarantine.

11:00 a.m. – Wake up

Wells said, “I’d go to bed late, wake up late. I didn’t have to wake up for the cafeteria or anything. I’d eat lunch if the cafeteria food that was delivered to me was good, or I’d make some cereal.”

1:00 p.m. – Procrastinate

“I’d call my mom. I cleaned my room and went through and got rid of stuff and even went through my emails. I would text my friends and ask them to bring me better food. Mostly, I would lose track of time and watch Netflix for a good while or FaceTime my friends and not even talk,” Wells said.

4:00 p.m. – Do nothing

“I just sat and did nothing. I looked outside and was bored all day. I would just lay around and be depressed,” Wells said. “I did workouts because I was feeling really depressed and needed dopamine.”

According to Mental Health America, reported cases of anxiety and depression reached an all-time high since the beginning of the pandemic and are especially prevalent in young people. Having already been diagnosed with anxiety and depression, Wells said the swell of emotions from isolation caused her mental health to plummet, and she struggled to find motivation.

7:00 p.m – Reflect on things

“I started a COVID sucks journal, which I wrote in a couple times.”

10:00 p.m. – Maybe do some homework

In regard to her assignments, Wells said she asked her professors for an extension on the first day of her isolation, but ended up setting aside emotions to be academically productive given all her extra time. This was especially difficult with classes already being virtual.

Wells said, “I was already doing school in my room so I had nowhere to escape to.”

3:00 a.m. – Watch more Netflix

4:00 a.m. – Go to sleep

In The Point’s efforts to inquire about combating mental illness amid isolation and quarantine, repeated attempts were made via email to contact PLNU psychology professor and licensed clinical psychologist, Kirstin Filizetti, with no response. Repeated attempts were also made to contact assistant professor of psychology Rosemond Lorona, who also did not respond.

Caye Smith, vice president of student development at PLNU, explained how a normal semester produces a “strong demand for mental health services; our Wellness Center counseling appointments are consistently full throughout every semester.”

PLNU provides 24 hour telehealth appointments accessible to all students through LomaCare. Smith said, “This service has allowed us to expand our mental health coverage and provide services throughout the country and around the clock.”

Smith said, “many sources suggest that the overall need for mental health services has increased during the pandemic. It is reasonable to assume that this is true for PLNU students as well.”

With the availability of mental health resources, it would only make sense that PLNU students would take advantage. But are they?

“We certainly do have requests for services, but the majority of our students are not on campus and appear to be getting their mental health needs met apart from PLNU resources,” Smith said. “So, I cannot say definitively that PLNU is seeing an increase in demand for mental health services due to the fact that most of our students are not on campus.”

For resources on mental health please visit:

A nonprofit dedicated to educating and empowering you to improve your mental health

A subscription based resource of articles, meditations, etc. to help you practice and understand proper mental health. While some content is free, the full version gives access to all content for $5.83 a month annually or $12.99 monthly.

Provides a plethora of mental health resources including specific to wellness and coping skills.

The National Suicide Prevention Line

If in crisis and needing immediate assistance in regard to mental health, this resource provides over-the-phone help. For English call 1-800-273-TALK (8255). For Spanish call 1-888-628-9454.

The Center For Disease Control and Prevention

The CDC has many resources available for stress and coping.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services AdministrationSAMHSA offers resources to help improve your mental health, including a behavioral health treatment services locator.

Written By: Charis Johnston