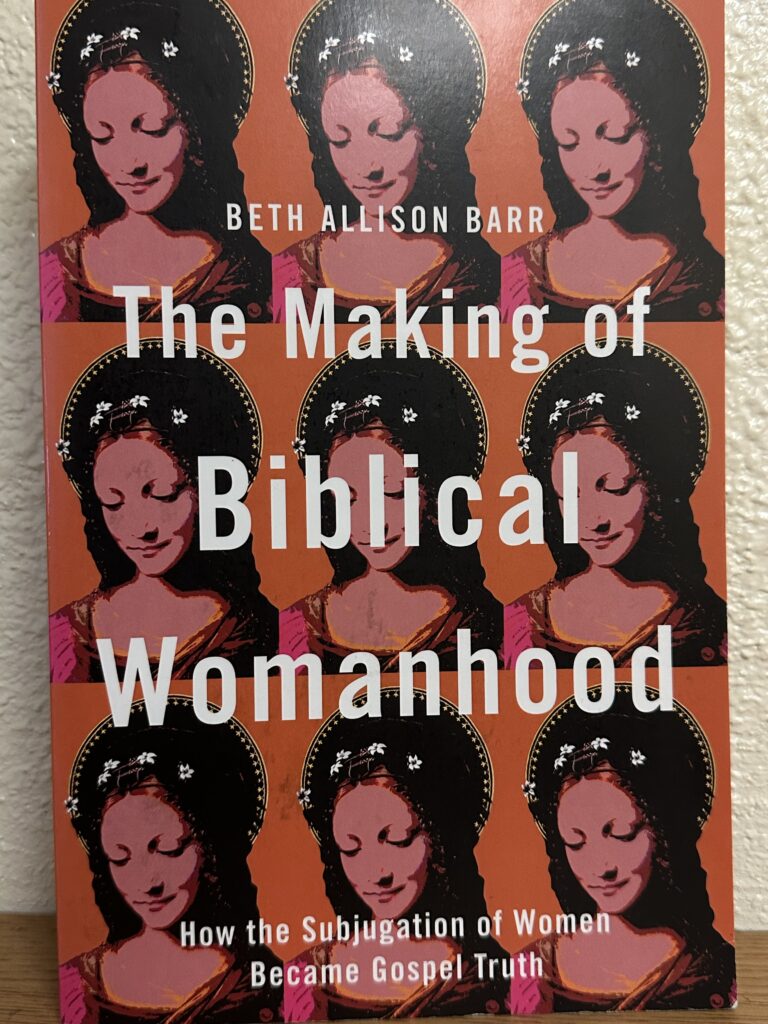

On Sept. 12, Beth Allison Barr, medieval historian, author of “The Making of Biblical Womanhood” and professor of history and associate dean of the graduate school at Baylor University, spoke at Point Loma Nazarene University’s annual Colt Conference.

Hosted by PLNU’s History and Political Science department, Barr spoke about how history has shaped the church’s understanding of gender roles. A reporter from The Point attended her lecture and spoke with Barr the following day about her book.

The Point: So just to start off, your book has been out for a couple of years now —

Beth Barr: Yeah, it came out April 2021.

TP: — I just want to know how you feel about its reception. In the introduction, you talk about how the words and this subject just flowed out of you. Did you think it was going to resonate with so many people?

BB: So looking back, when I wrote that in the introduction, it was about a blog post that I wrote when I went home after church one day. That did just flow out of me. At that time, I had no idea I was going to write a book about it. When I did actually decide to write the book, I had no idea what was going to happen with it. I honestly thought it was going to be something like a slow-burner. I even remember looking at my contract and it had these stages where your royalties went up depending on how many books it was, and I remember being like “Oh my gosh, I’m never going to reach any of them.”

My hope was that it would start to be something that people would just begin to pick up and read over time. And over time it might help to change the conversation. I figured it would just join with a lot of the other texts that are out there, so it was really surprising to me that it took off the way that it did. I wasn’t prepared for it, by any stretch of the imagination. I was still a dean when the book came out. I was in a meeting that day and I got an email from NPR and I got a direct message on Twitter from Eliza Griswold, who is a writer for the New Yorker, and I got another email from The Holy Post with Phil Vischer. I got them all within 10 minutes of each other.

I went and sat in my office and I was just like, “I don’t know what’s going to happen.” That was the moment when I was like, “This is going a lot bigger than I ever imagined.” So that was when I had to grapple with it. But overall, I’m really happy with the reception of it.

If you write a book, you want people to read it. So the best thing that can happen is to have a lot of people reading and engaging with it. Even if they all don’t agree with it, that’s fine, because they still have to engage with it. Even if their engagement is negative and they want to argue against it, it is still showing that they think it’s important enough that they have to defend against it. So I don’t think I could have asked for a better reception of the book, with both the good and the bad, because people have engaged [with] it.

TP: Something I really appreciated after finishing reading the book was feeling like I finally had the language to express something I had been feeling for a long time. I think it was powerful for me to actually be able to point to historical facts and evidence. I’d love for you to share what exactly it is about engaging with history and re-learning history that is so important and impactful in faith communities.

BB: I’ve heard that from a lot of people: that they were uncomfortable with what they were being taught in church, that they would see discrepancies in the Bible with what women were doing and then what they were told women could only do and it wouldn’t make sense to them. But almost everything they had known left them with this idea that that was what biblical womanhood looked like. So they didn’t really have an alternative.

What my book did was actually show how this particular model of biblical womanhood was built. I think when you show somebody how something is constructed it gives them permission to show how to deconstruct it. That’s where the word deconstruction — that people are all so afraid of — is just showing that things are built into culture. If you know how they are built, you know, at least theoretically, how to un-build them. I think that’s what history does; history helps us understand that events are not inevitable events. There are reasons that something happened, and often those reasons are a lot deeper than perhaps we had imagined. Like for example, biblical womanhood, with the roots going back all the way to the Reformation era.

It gives you that, and it helps you understand how things work. For me, that’s what I love about history: that it helps me understand how a culture works or how a particular geographical area works. I think that’s what this book did for people. It helped them understand not only how what they were being taught in the church was built, but also how it [biblical womanhood] worked to convince women that this was what it was supposed to be.

As I said, I think in general that’s what history does for people. I think there’s a lot of power in understanding that nothing is inevitable, that it has been created for particular reasons. Which means even for things like racism, they can be dismantled if we work at it.

TP: So, you touched on the word deconstruction earlier. I thought it was interesting how we are presented with the title “The Making of Biblical Womanhood”, but you also talk a lot about “un-making” biblical womanhood. To me, that screams deconstruction. After all of that un-making, or deconstruction, that you had to do personally, was there any room for reconstruction? After all of that tearing down, how did you think about building things up?

BB: So the original conclusion of the book was supposed to be “re-making biblical womanhood.” That was originally what the last chapter was supposed to do. By the time I got to the last chapter, I was like, I don’t want to tell anyone how to be a biblical woman. That’s my whole point, that I believe God gifts us individually and there’s no specific pattern.

I know it’s popular to want to give people a plan on how to rebuild something, but I don’t want to do that because my whole point is that we are free to be whatever God has called us to be. As I said, I didn’t come to that [realization] until I got to those last few chapters. I was like, “Yeah I’m not going to do that.” So I wrote my final chapter based on suffrage, really. That’s what was in my mind the whole time I was writing it, that it’s just simply time for women to be able to do whatever God has called them to do.

Looking back on it practically, I think there does need to be some changes. How do we practically implement this? I think there is still work to be done with that. I’m not sure if I’m the person to do that work because I think history tells us how we got where we are. It doesn’t necessarily tell us what to do with that.

There’s actually a really good book by a sociologist named Lisa Swartz called “Stained Glass Ceilings,” which compares an egalitarian seminary with a complementarian seminary. It shows how even in the egalitarian seminary, even though they support women in ministry; they haven’t changed their structure or their culture. So there’s actually less empowerment of women in egalitarian spaces than in complementarian spaces. It’s really fascinating.

I think books like that help us to understand how to rebuild when you think about sociologists. I think there’s other helpful people when I think about how to rebuild. At the end of the day, I just don’t want to tell people how they have to be.

TP: I appreciated reading about all of your connections to and history with the Southern Baptist Church. I don’t think everyone knows how strong the rhetoric of complementarianism can be if you haven’t been a part of a church that preaches that. But that was something that you lived within and engaged with on a regular basis. To what extent does your own history with that church and that narrative influence how you engage with those who oppose you, and how you enter into those conversations?

BB: I think it has given me a lot of generosity toward why people remain in complementarian spaces, and also a lot of understanding for people who continue to believe this. Because they honestly believe that this is how women are to be, and so these are ideas that they are faithfully following through. I don’t think it’s my job to tell them not to believe that. I think my job is just to help them understand that there are other faithful Christians who believe something very different about women.

So I think it has given me a lot of generosity, but it also has made me more frustrated with the people who are more complicit in it. By that, I would point to the sort of architects of this. You can think about Al Molher, and some of these folk who helped to write these structures, [who] refuse to see any other way and couch anyone who disagrees with them as not believing in the Bible. That’s the narrative that they’re trying to spread. So I find myself more and more frustrated with the architects of this. Especially since some of the architects are still living. It’s just insane how recent this modern form of complementarianism is. A lot of them are still alive. It’s like they knew what they were doing, so I have a lot less patience with them.

A third piece in this too, as much as I understand why people believe in complementarianism and how much I try to be generous and never question anyone’s faith, is I find it frustrating because I know the damage that complementarianism can do. Especially to women who are hurt by it and don’t have the tools to understand what has happened to them, nor the tools to move out of those systems.

I think especially of Dorothy Patterson, Paige Patterson’s wife. There’s this really horrific audio of her teaching a class at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in which she tells a story about a woman who came to her and told her that her husband was abusing her. She [Dorothy] told her that she needed to apologize for whatever she had done that had driven her husband to that behavior. And that is just shocking, to know that women are being told things like that. And the damage that it can do to them. So I think I’m really frustrated with that.

TP: Just something I felt like was a theme over and over again in the book was seeing institutions trying to dictate people’s bodies, and how people exist. It’s this idea of sanctifying motherhood as this holy role, with some sort of extra emphasis on it – what’s going on there? With that elevation of a domestic role, and the childbearing role, what’s so dangerous about that?

BB: I think there’s multiple dangerous aspects to that, but one of them is definitely that not all women can fulfill this role. If you were told the way you will be saved is through childbearing, to misquote Timothy, if you were told that and you can’t have a child, or you don’t want to get married, anybody who does not fit into that box, what they are being told is that they are not fulfilling their divine role. And the damage that does – I can’t even imagine the damage that does to women who don’t fit into that box.

I also think it makes the church speak only to one segment of their congregation. The church is much more diverse than that. The church becomes only for people who look a certain way. You can kind of think about it as Instagram posts; Instagram is all of the best parts of our lives, and the church kind of becomes like that. It’s only people who fit this model of what it means to be a biblical man or woman, and everyone else is shamed. It’s a culture of shame. That’s a big problem.

I think the other problem with it, is that we know the emphasis placed on motherhood in the post-World War Two era was about a response to World War One and World War Two, in response to population building and also a response to helping get men back in the workforce. And so in order to do that, they felt like they had to push women out so that they wouldn’t be competition.

So, this is where we get these very strict ideas of domesticity. I think where they [those ideas] got a lot more power was in this postwar era. It’s such a culturally specific timeframe. Again, it is one that does not apply to everyone. And it only applies to privileged households that can afford only one person working and/or middle-class families that try to uphold this idea of biblical womanhood to the detriment of their family.

I mean, think about the ones where the wife really is the much better breadwinner and the husband is not, and [he] would much more likely want to stay home? And that’s something that they felt they could do but is not really acceptable in Evangelical culture. Although more men are doing it, [but] it’s not acceptable.

TP: Toward the end of the book you talk about the phrase “fundamentalist-modernist controversy,” and you talk about how that was really a conversation about the nature of biblical truth. This is something I’ve encountered, that argument of, “oh, well, if you’re interpreting this verse in context, or if you’re rejecting this, you might as well just throw away the Bible,” which is a very slippery slope argument. How do we, when we encounter those kinds of counter-arguments, how do we challenge those? Is there a way to really effectively engage with people that hold those beliefs?

BB: So I mean, again, history helps us understand this, that this was a response to the late 19th century, with growth in scholarship methods about deconstructing the biblical texts and having a better understanding of the context of the creation of it [the Bible]. With that also came a narrative that, if the first five books of the Bible weren’t written by Moses, then that must mean they’re not true. Even that approach is misunderstanding the type of historical text that the Bible is. But yet, that was the idea. It was a response to this German higher criticism. And it was also a response to Darwinism. People were terrified of this, you know, this growing understanding that the world is maybe a lot older than we thought it was. And that the creation narrative happened, in a different way than what people who do a literal reading of Genesis [think].

I think that caused a lot of fear. And so ultimately, to boil it down, the fundamentalist-modernist controversy was over people who were much more willing to accommodate the Bible to culture, versus the people who said, “We have to read it literally as it is now. And we have to draw the line here.” And I think both sides went too far with that, which is often the case.

But, how do we deal with people who believe that? I think we have to deal very gently with them. People who are told that if they believe the creation narrative in Genesis didn’t happen exactly like that, or if they don’t believe that, then their faith is worth nothing? What happens when they come to that realization that there was more to the creation story?

What they have been taught is, that’s the end of their faith. And I think this type of fragile understanding of faith doesn’t help people pick up the pieces. I think a lot of what we’re seeing and sort of, you know, I don’t want to go too far. But I think we’ve seen a lot of public stories of people who were in these very rigid understandings of how the Bible worked. When they hit up against walls where they realize “Oh, this can’t be true,” they lost it all.

That’s what they were taught to do. So we don’t blame them. But they didn’t have anybody to help them pick up the pieces. You know, like, what do you do? And so I think it’s really important to point people to — like last night, I talked about Wil Gafney and she is a scholar who was probably a lot more progressive. However, she is a firm believer in Christianity and the Bible. And so I think she’s a really great example to show that yes, you can be a firm Christ follower, and yet have a different understanding about how the Bible works. And it doesn’t mean everybody has to agree with that. But it’s good to know that people can believe something not exactly like you about the Bible and then still be part of the church.

I think the story that really helped me with that, because I have come to see that the people that I study in the 15th century were those who believed something very theologically different than I do, but I don’t question their faith that I see. And their belief is in the same God that I believe in, even though my understanding of that faith is different than theirs. So I think history also helps us with that. [We can be] Generous toward the fact that we don’t know everything, and we might be wrong.

TP: Speaking of using history to kind of combat misunderstandings, something else that stood out to me was when you talked about encountering heresy in the church — in the message about Jesus being subordinate to God, and how that in itself is used to justify a lot of patriarchal arguments. Your work as a historian helped you kind of push back on that. Have there been other times, whereas you’re engaging with history, you’ve realized like, oh, this is a heretical belief — beyond biblical womanhood? Have there been other times where you’ve encountered history and what’s being taught in church not lining up?

BB: Yeah, that’s a very interesting question. So I think that probably the biggest one — you know, I don’t think we should use the word heresy lightly. And I’ve gotten a lot of criticism for calling it heresy or equating it with Arianism. Some people want to nitpick about what Arianism is. But it’s, you know, essentially, from my historical understanding, Arianism has become this catch-all phrase for Jesus not being fully equal, eternal with God the Father. And so anything that puts Jesus as less than God is putting Jesus in the camp of a creative being. So, I feel very comfortable with my use of Arianism [as heresy].

I would say probably in the church, though, we don’t understand the Trinity well. I think we’ve forgotten to teach about the Trinity. I think there’s probably a lot of misunderstanding about the role of the spirits because there’s some traditions that teach it really well. And there’s some traditions that almost ignore it. In fact, with ESS [eternal subordination/submission of the Son], I think one of the worst manifestations of it is the idea that the Holy Spirit is born of God the Father, or almost proceeds from both God the Father and God the Son. But I’ve seen a depiction of it, where the Holy Spirit is like the child. And that’s really, you know, I think anytime we try to put things into human metaphors, we can mess it up.

I think another heresy that I did actually talk about in the book, I didn’t call it heresy, but this [idea of] putting the father, putting men in the role of not just priests but also Jesus. And there was a really interesting study that talked about how when women and men heard stories from the Bible about Jesus when men hear them in Evangelical churches, they often see themselves in the role of Jesus, and the disciples. Whereas when women hear [stories], they don’t see themselves [as Jesus or the disciples]. So I mean, there’s something dangerous when you hear a story, and you see yourself in the role of God.

I think that lends to a lot of these ideas about how we teach the gender of God, in the church, I think there’s a lot of potential heresies around: What does it mean that we have God the Father language that’s used?

Amy Peeler has done a brilliant job in her most recent book on the gender of God, and helping us understand why that imagery is used, and how to not be heretical with it. But I think anytime we equate God with maleness, or with femaleness, we are making God like us instead of trying to be more like God.

I do see a lot of historical patterns in the church for Protestants who argue that there shouldn’t be worship of the saints. I think it’s really weird how we revere pastors like John MacArthur. I knew a pastor once who built his office to resemble John MacArthur’s office. And then he had a picture of John MacArthur by itself on a table and I’m like, isn’t this a shrine? This is strange. Why are you revering this man in this way? So I think as much as we resist the language of sainthood, we make our own saints in Protestantism. I think that’s one of the dangerous things. It’s funny how they manifest in different ways, but often we come up with a lot of similar ideas, which is always interesting.

TP: So just to wrap up, one of the big conclusions is that by preaching patriarchy, the church is acting as a reflection of the world instead of in opposition to it. Just kind of go big picture, beyond biblical womanhood, have there been other times where you’ve seen this? Are you encountering other things where you feel the rhetoric of the church is actually acting as a reflection of the world and not maybe challenging it?

BB: Oh, there’s so many different examples of that. I think that’s why people are so afraid of this, because they use the slippery slope mentality. But my thought is, well, if you are on the wrong slope, maybe you should slide off of it. If you have built your own idea of who God is, and that’s wrong, maybe it’s time to move.

I think there’s a lot of fear, obviously, in that. I think the church has lost its understanding of hospitality, and its understanding of being able to work with people who are different from us. We can think about diversity, we can think about sexuality, and we have become much more likely to shut people out than to invite them in. And it seems strange to me because one of the major themes we see in the Bible is this theme of hospitality and inviting people who aren’t like us to meet God. I think whenever we find ourselves more likely to exclude that maybe we should re-examine what’s going on.