Editor’s Note: Per Marty Decker’s request, details of his statistics have been added. During his college career, he had three one-hitters.

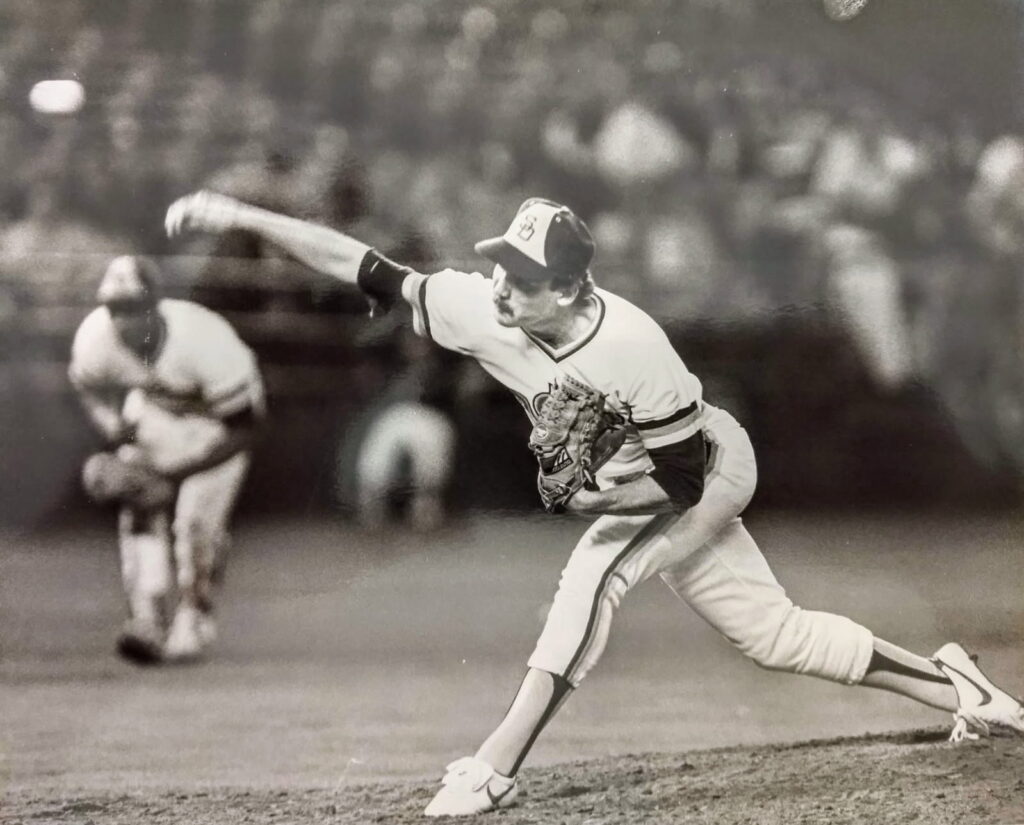

The sound of his cleats digging into the dirt as he ran up to the mound was routine; he’d done it hundreds of times. His eyes locked on his throne as he thought: “We got nine innings. Let’s get this done and go home.” He wasn’t stepping off until they won the game – losing wasn’t an option.

“He was not going to leave that field. … He was not coming off that mound,” Ron Swen (‘82) said.

Marty Decker’s number is one of the two retired baseball jerseys in Point Loma Nazarene University’s history. There are no plans to retire another, according to Jordan Courneya, PLNU’s interim athletic director. This leaves Decker and the late Carroll Land, who died in 2021 – the other retired jersey – to reside together on the field for the rest of time.

Decker had a father-son relationship with Land, a PLNU baseball alumnus who played while also serving as the head coach in his final year. He said he considered him a Christian mentor who taught him life lessons, not just how to play better baseball.

“His baseball field was his sanctuary,” Decker said with a trembling voice. “Everybody knew – everybody knew where Coach Land stood with the Lord and how he expected us to be.”

The baseball stadium was named after Land, who had coached for 39 years, in 1988 to honor him for building up the program from the Pasadena location to Point Loma. To recognize him further, PLNU wanted to retire his jersey. According to Decker, Land said there was one condition to allow the university to do so: to retire Decker’s, too.

In 2008, the two jerseys were retired together.

Decker is considered one of the most stunning pitchers the university has ever had. He holds pitching records, including most wins in a career (37) and season (11), most career innings (495) and most career appearances (89).

He’s still PLNU’s leader for most strikeouts in a game, season and career. He also had three one-hitters and one no-hitter. He pitched to an ERA (earned run average) of 2.16 and was a three-time All-District, All-American performer. He led his team to the playoffs every season he pitched. pitched.

“When Marty started the game, his intention was to be there until the last pitch was thrown,” Swen said, who played two seasons with Decker. “His competitiveness was unrivaled. He was just an incredibly intense competitor.”

Decker was drafted into professional ball out of college.

The legend has since replaced his pitching glove with a mic. He now stands in front of a congregation instead of the opposing hitter. And instead of leading his team to victory, he’s leading the church to what he considers the greatest victory of all: life with Jesus Christ.

Decker began playing baseball at 7 years old. His dad took him to a Dodgers game, and he was hooked, he said. His dream was to play professional baseball, but the only college interested in him was a junior college that would require him to redshirt.

“Not many people know at that age what they want to do in life, but I knew, and somehow I just knew it would happen,” he said.

His dad, who was a Nazarene pastor, convinced him to attend PLNU – named Point Loma Nazarene College at the time – to play for the team.

PLNU legacy

According to John McGaffey (‘80), who played two seasons with Decker as his catcher, Decker was a “problem child” early in his college career, but Land kept him straight.

“They had probably the closest relationship of anybody on the team,” McGaffey said.

Decker wasn’t always a pitcher. In fact, he never wanted to pitch, he said. Even throughout college, Decker fought Land to play the field, but Land refused, until his fourth year when Land let him hit – it was a home run.

“He let me play the field a little more from then on,” he said laughing.

There was a strong mutual respect between Decker and Land, he said. Decker recalled a game where Land was going to take him out and he refused: “You’re not pulling me out,” Decker said he told Land. “Let me get through this and let’s go home.”

McGaffey said that Decker wasn’t like other pitchers who may have been inexperienced; he wasn’t afraid to reject a pitch if he didn’t like it.

“Marty was very confident; he knew exactly what he wanted to throw – to who and where,” McGaffey said.

He said they had their own signals no one, including Land, knew about to communicate on the field.

Decker was named Freshman Athlete of the Year his first year and in his third, second team All-American and received the university’s Meguiar Award – a scholarship for the most outstanding athlete of all sports.

At the heel of his successful third year, he and another teammate were joking around playing lumberman, while on a project Land had given them to set up telephone posts, and he fell, tearing every ligament and tendon in his ankle. He couldn’t play his final season.

“It was devastating for the team,” Swen said, “because whenever Marty took the mound, you knew that you were going to win the game; that’s just the way it was. … He just wouldn’t take ‘no’ for an answer.”

Land insisted that Decker take the year to heal, and extended his scholarship so he could play another season, and he did.

He returned for his final year, in 1980, even better. He was named first team All-American and was drafted into professional baseball along with McGaffey.

Professional baseball career

McGaffey was picked by the Los Angeles Angels in the 12th round and Decker by the Philadelphia Phillies in the 23rd round.

They both went to the same league in the north as Decker was in Montana and McGaffey in Idaho for rookie ball, so they competed against each other and would grab dinner afterward, McGaffey said.

“It was always fun because he wanted to strike me out and I was not going to let him strike me out,” McGaffey said laughing. “It was a draw between he and I.”

After a successful season in Montana with an ERA of 2.08, Decker was bumped to High-A ball.

For winter ball, he played in Hermosillo, Mexico, where he got to pitch with the late Fernando Valenzuela, who played in 17 Major League Baseball seasons.

For the 1982 season, Decker was sent to Oklahoma City to play for the 89ers. About three weeks in, he experienced elbow issues that resulted in a season-ending surgery.

After spring training in ‘83, he moved to Oregon to play for the Portland Beavers, the AAA affiliate – the highest level in the minors – for the Phillies, and won the Pacific Coast League. Later that season, he found out he had been traded from the Phillies to the San Diego Padres – where he leapt into the majors.

After winter ball in Caracas, Venezuela, Decker’s elbow injury flared up. He spent a year and a half trying to heal, but nothing was left of his joint, he said.

Decker’s elbow formed bone spurs that damaged his ulnar nerve – which helps you move your forearm, hand and fingers. On his second operation, he discovered his elbow capsule had disintegrated and had 13 pieces of synovial tissue removed – which protects your joint when you bend your arm. As a result, he was and still is not able to flex or extend his elbow.

While only appearing in four games for the Padres, Decker pitched to an ERA of 2.08 and had nine strikeouts in 8.2 innings of work.

While devastating having his time in the major leagues cut short, Decker said it steered him on his path to ministry.

“I was not following after the Lord when I played pro ball,” he said. “Had I stayed … I never would’ve heard the call of the Lord into ministry.”

From baseball to ministry

Decker was raised as a pastor’s kid. And he said he swore he would never be a pastor because he didn’t like organized corporate religion.

In 1986, he moved to Yuba City to be closer to family, opened a pizza shop and met who would become another Christian mentor for him: Joe Strawmier, who challenged him to form a relationship with God.

On the way to a hospital visit with his dad, Decker said he heard the voice of the Lord: “Fill in for your dad.”

Decker’s father was a pastor who spoke once a month at Grimes Community Church and was supposed to preach that weekend but wasn’t able to. Slowly, after a few more Sundays, Decker became the church’s full-time pastor, where he still is today.

When Decker had to let go of baseball, he said he was stuck trying to figure out what was going to excite and motivate him like it did. When he found himself in ministry, he said the Lord was the reason for his existence.

“I have no regret that I only had 11 days in the major leagues,” he said. “I would have huge regrets if I didn’t have my 25 years in ministry.”

Decker resides in Yuba City with his wife, Julie, and has five children: Haley (45), Dusty (43), Amber (36) and two step sons Randy (39) and Ryan (32), along with 10 grandchildren.

Decker, Swen and McGaffey have remained close friends over the years, they all said.

“If we could be together every day, we could because we just enjoy each other’s company so much,” McGaffey said. “We just end up laughing the whole time we’re together.”

Decker, Land and McGaffey sit together in PLNU’s Hall of Fame.

“The years at Point Loma were some of the best years of my life,” Decker said. “I wouldn’t have traded them for anything.”

Since retiring 17 years ago, Decker’s #27 and Land’s #36 still stand together, like they once did, watching the 45 teams that have gone through since their last performance in 1980.